One of the natural history mysteries I investigate is the retention of dead leaves over the winter in certain plants, such as beech and oak. The leaves are not photosynthesizing– so why do plants retain them? I’ve found that leaf retention may influence herbivore density and diversity in the spring (Pan et al. 2021) and may even promote baculovirus transmission among herbivores (Pan et al. 2023).

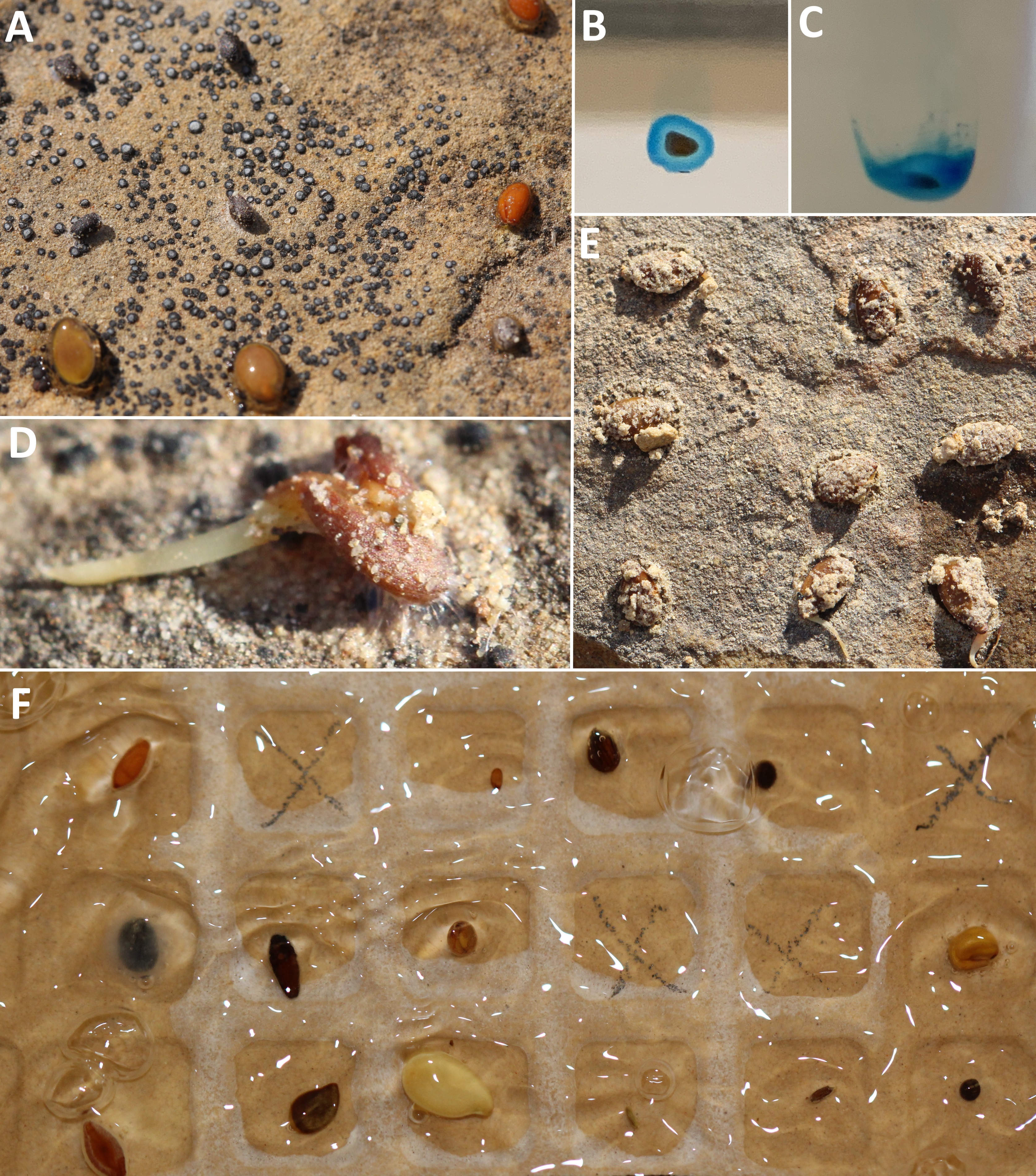

I also collaborate with Eric LoPresti at the University of South Carolina to explore the functional ecology of seed mucilage. Seed mucilage, or myxodiaspory, consists of sticky sugar secretions produced by seeds that act as a powerful adhesive. This trait is found in thousands of plant species and has evolved independently across multiple lineages. On loose sand, seed mucilage forms a “sand-armor” that protects seeds from predation by various granivores (LoPresti et al. 2019; LoPresti et al. 2023). On harder substrates, the mucilage binds seeds so securely to the ground that neither granivores nor surface flows during rainstorms can dislodge them (Pan et al. 2021; Pan et al. 2022).

Another natural history mystery I explore is the maintenance of floral color polymorphism in dame’s rocket (Hesperis matronalis). In the wild, both purple and white flower morphs often grow side by side, raising the question: what drives the varying ratios of these morphs through time and space? To investigate this, I’ve been studying 40 local populations of H. matronalis in Michigan and analyzing iNaturalist and herbarium records. Preliminary findings suggest that niche segregation and frequency-dependent selection, influenced by climate anomalies and herbivore pressures, may be contributing to these patterns.